Bayesian linear calibration with iid priors

a theoretical and practical guide

summary

Bayesian calibration is a great way to fit a model to data when you want to know something about uncertainty in your model, while also collecting info that is useful for model development and updating purposes. Linear calibration is a very common subgenre of Bayesian calibration that we need for instance when we want to fit a model constructed from basis functions. The functions themselves need not be linear or even closed-form, and the right basis set thus opens a wealth of options for model building and updating. This post reviews the process of Bayesian linear calibration for a context in which we are fitting a new model to data for the first time.

intro

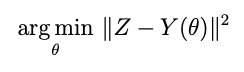

Most of us in science and engineering are familiar with the process of fitting a model to data. We often refer to the process of gathering data and fitting an appropriate model to it as a “measurement” of one or more parameters appearing in the model. Such fittings often happen in a way that yields a single “point estimate” of parameters — those parameters for which the model conforms to the data closest in some sense. Often this is the minimum point of a least squares cost function:

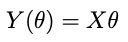

where Z is the data, Y is the model with θ the model parameters. We can use an optimizer for this, or if the model is linear in the parameters —

where X is an NxP matrix with N the number of datapoints and P the number of parameters — then the optimum point is:

But obtaining just the optimum point leaves out a lot of potentially useful information. One of the most important questions is: how much confidence is there in the optimum? Is the shape of the cost function sharp or kind of flat there? This question becomes even more critical as the number of parameters increases. Even in a linear fit, some of the parameters may be confidently estimated while others may be highly uncertain.

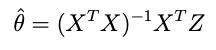

A Bayesian approach is a way to answer these questions by effectively obtaining more information about the shape of the cost function near the optimum. This information comes in the form of a probability distribution for θ, which gives us a quantitative measurement of the uncertainty in our parameter estimate.

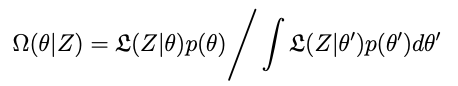

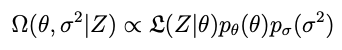

The distribution we want is created from the data, the model and some prior information about what θ is, according to Bayes rule:

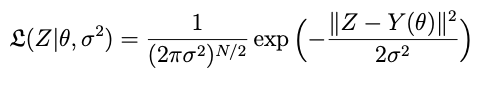

where 𝕷 is (often, though not necessarily) a white noise likelihood with variance σ²:

and p is a prior probability distribution for θ, which may be vague (that is, just a uniform or wide-variance normal distribution) or stronger if we have more a priori information. The likelihood is a density quantifying the probability of having measured the data that we collected given the physical and error model parameters.

Given σ² and p we have the posterior distribution Ω in principle. Only a couple of problems:

We usually don’t know σ². Instead what we usually have is a noisy dataset that we are trying to fit with a model. Surely that model will have some bearing on what we think the noise is vs. variations due to the underlying process we are trying to model. And — this is key — that assessment will change as we change θ

We need to figure out how to integrate the denominator in the expression above for Ω — this is the normalizing constant of the distribution. It’s relatively easy to evaluate the numerator, but without the constant we have no (immediate) way of knowing how important that point is in the distribution.

The solutions to these problems are:

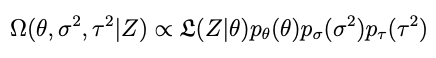

Make σ² another parameter we estimate from the data. This means it will be another component in the distribution Ω:

Choose the priors wisely so that we can integrate the denominator and obtain a closed-form solution for Ω.

Task number 2 takes some thinking. First, its not possible for just any Y. But it does work when Y is a linear in θ.

conjugate priors and conditional posteriors for linear models: θ

Let’s consider the two components of the distribution in turn — θ and σ² — imagining that we hold the other constant. If we can find the right conjugate priors for each, we will have closed-form solutions for the conditional distributions pertaining to the other parameters, meaning that we can perform iterative sampling in a way that quickly converges to a representative sample from the overall distribution.

First, θ: what kind of prior will combine with the likelihood so that we can integrate Bayes’ Rule when we are holding σ² constant? To figure this out we aren’t actually going to evaluate any integrals. Instead we’re going to compare proportionalities to distribution forms we know already. Why do it like that? Because it’s easier than integrating. We know it works because the full posterior (above) is normalized, and thus we know that the conditional distribution will be properly normalized as well. We can sample from it so long as we recognize its form from the proportionality.

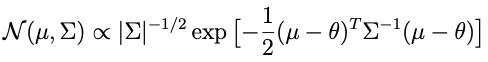

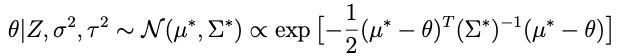

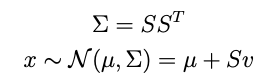

What remains is to choose a prior that combines with the likelihood in a way that takes the form of a distribution we recognize. Somebody at some point figured out that the prior for θ which is conjugate to a white noise likelihood is a multivariate normal, and that the corresponding conditional posterior is also multivariate normal. Multivariate normal distributions have the following form:

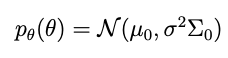

where μ is a mean vector and Σ is a symmetric, positive-definite covariance matrix. The prior that works is:

where μ₀ and Σ₀ can be anything. In particular these can be the mean and covariance matrix arising from some previous fitting exercise, and we can be updating that model with some new data.

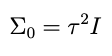

But for the purpose of this post let’s imagine that we are fitting a model for the very first time, using an efficient, orthogonal basis centered on the origin, so that our *completely naïve* prior mean μ₀ for the coefficients is the zero vector. Let’s also imagine that this basis is ordered, such that higher terms in the expansion drop off all by themselves without having to make the coefficients do that. This means that the prior variances for those coefficients can be independent and identically distributed, or iid. With these assumptions, we can write the prior covariance matrix in a simple form:

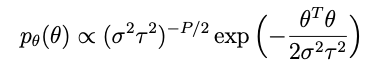

where I is the identity matrix and τ² is a scalar representing the variance of the data. Combining the last two equations we write the independent and identically distributed prior for θ:

where P is the number of terms we have (i.e., the length of the θ vector).

OK so but — whats τ² ? Again, we don’t really know. In a Bayesian context a good thing to do when we don’t know what a parameter is exactly is to put a prior on it representing the vagueness of our understanding and let it be estimated as part of the calibration. So we’ll do that:

But for now let’s keep focusing on the conditional posterior for θ, meaning we assume τ² and its prior are constants.

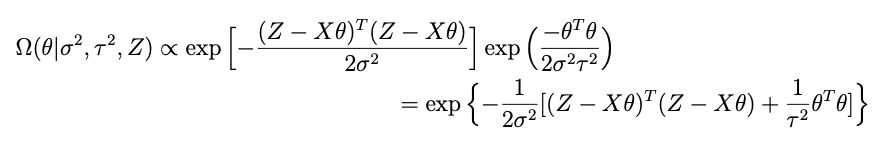

Combining all of the terms that have something to do with θ while forgetting about the rest, we get:

Remember we need to find a μ* and Σ* such that

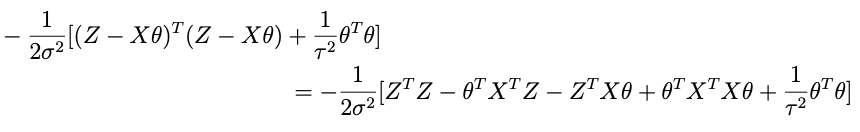

so lets take apart the exponential above to see if we cant get something resembling this. Here’s what’s inside the exp:

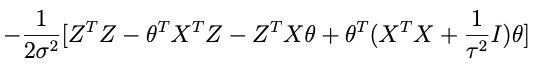

if we combine the last two terms we get:

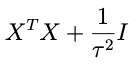

sohey that thing in parentheses:

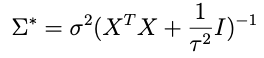

is looking like a pretty good candidate for the inverse covariance matrix. Let’s try it and see what happens. That is, let’s assume that

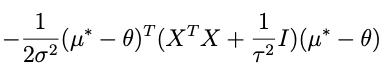

and plug that in to the expression above with μ*. When we do that we get this inside the exponential:

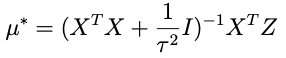

we need to choose μ* so that it matches what’s captioned ‘equation A’ above. One crucial thing to note: any term in this expression that doesn’t involve θ — like the term that only involves Z — doesn’t matter because remember we only need to get the proportionality right for θ right now. With that in mind an inspired choice for μ* is:

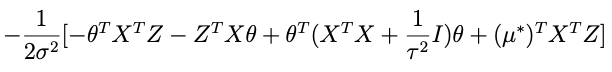

which, when substituted into the expression above, yields:

Where the last term there: no θ, doesn’t matter, since it will be normalized out. Lop that term off and compare with equation A above (minus the Z-only term) and we can see that it’s done.

fast sampling from a changing multivariate normal distribution

Given this μ* and Σ* we can set up a scheme for sampling θ. But let’s be careful about it: many built-in samplers may do the job relatively quickly, but in our case, Σ* is going to change every time we draw a new τ² (which we will get to soon) so we have to bear that in mind.

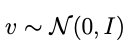

Generally speaking we sample from a multivariate normal distribution like this:

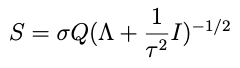

where

is a vector of iid, univariate normal draws. A key thing here is that S can be ANY factorization of Σ — usually it’s the Cholesky factorization but in our case it’s better to use an eigendecomposition.

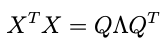

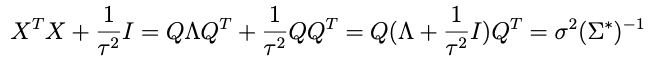

Why is that? Because of τ². Consider:

is the eigendecomposition of XᵀX. Now check out this trick:

which works because the transpose of a decomposition matrix Q of a symmetric matrix is equal to its inverse. So this means that:

Thus: even though τ² is going to change every draw, we don’t have to decompose the new Σ* every time. Instead, we eigendecompose XᵀX once and simply modify S (and μ*) as above for each new draw of τ²

conjugate priors and conditional posteriors for linear models: σ² and τ²

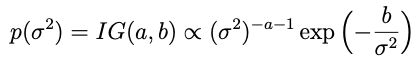

Alright so now we have a draw for θ and we need to move to σ². In this case the conjugate prior turns out to be an inverse gamma distribution:

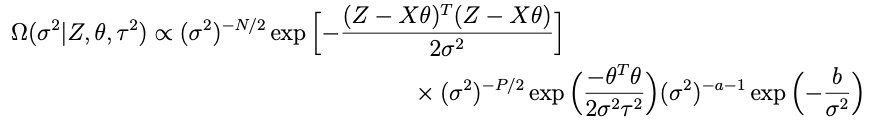

Now lets look at the terms in Ω that involve σ²:

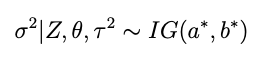

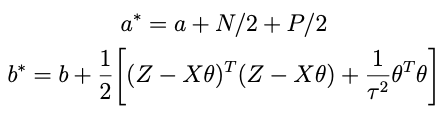

with a and b now the prior shape and scale parameters for σ². After some analysis similar to what’s above it becomes pretty clear that the conditional for σ² is

with

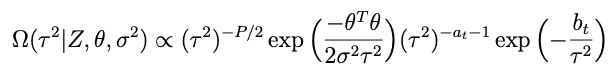

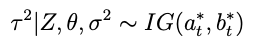

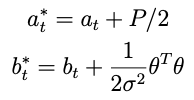

How about for τ²? The conjugate prior is also inverse gamma:

such that the conditional posterior for τ² is

with

advice on getting it running

Probably the most difficult thing is choosing the priors for σ² and τ². Fortunately, the data can help with this (hardcore Bayesians may disagree but at least some of us think this is okay). The good news is that our guesses don’t have to be right on the money, since the data (if there’s enough of it) will help us out. For this we can take advantage of the fact that the mode of the prior for σ² is b/(a+1). If you want to leave things pretty open, set a = 4. Then choose b such that the mode is equal to whatever you think the variance might be. Of course if you have some prior estimate (for instance that a vendor might provide with equipment) of what σ² should be, use that. The higher your confidence, the higher a should go (scale b accordingly).

Next choose your at and bt. Those should be set such that σ²τ² at the modes for both σ² and τ² is equal to the variance of your dataset overall (use the mode of the distribution you just chose for σ² in that calculation). Again at = 4 is a good default choice.

With the priors chosen you can now set your iterations off and running. Start each variable at the mode of its prior. if you choose priors well, it will converge fast: as a guideline, use around 1000 draws for burn-in and an additional 1000 draws as your distribution. Always check for convergence of your sample — meaning, that it settles around a consistent mean and variance for each parameter.

conclusion

That’s it! Did this help you? I hope it did. If so, please share it. Send praise / criticism / questions to me on Bluesky (@terencetrentdavey.bsky.social) or Linkedin, or leave a comment here.

Much love,

-Dave